It carries tiny passengers we don’t see, quietly moving from the hob to our lungs, and from there into the bloodstream. New research is tying that everyday indoor fog to two big killers: lung cancer and heart disease. Not from factory chimneys. From home.

It’s early evening and the flat smells like dinner and disinfectant. A pan hisses, onions catch, a child swings his legs at the table, and the extractor fan sits idle because it roars like an old bus. The windows are shut against the drizzle. A budget air monitor on the shelf flickers from green to red as the room warms, numbers ticking up each time the oil spits.

We rarely think of breathing inside as a risk, more like the pause after a long day on the pavement. Yet the evidence is stacking up, room by room, meal by meal. Fine particles from cooking, fumes from gas hobs, smoke from candles and wood burners, cleaning sprays that smell like citrus. The house carries all of it. The air we can’t see is the air that stays with us.

And this is where the story turns.

The new warning from inside our homes

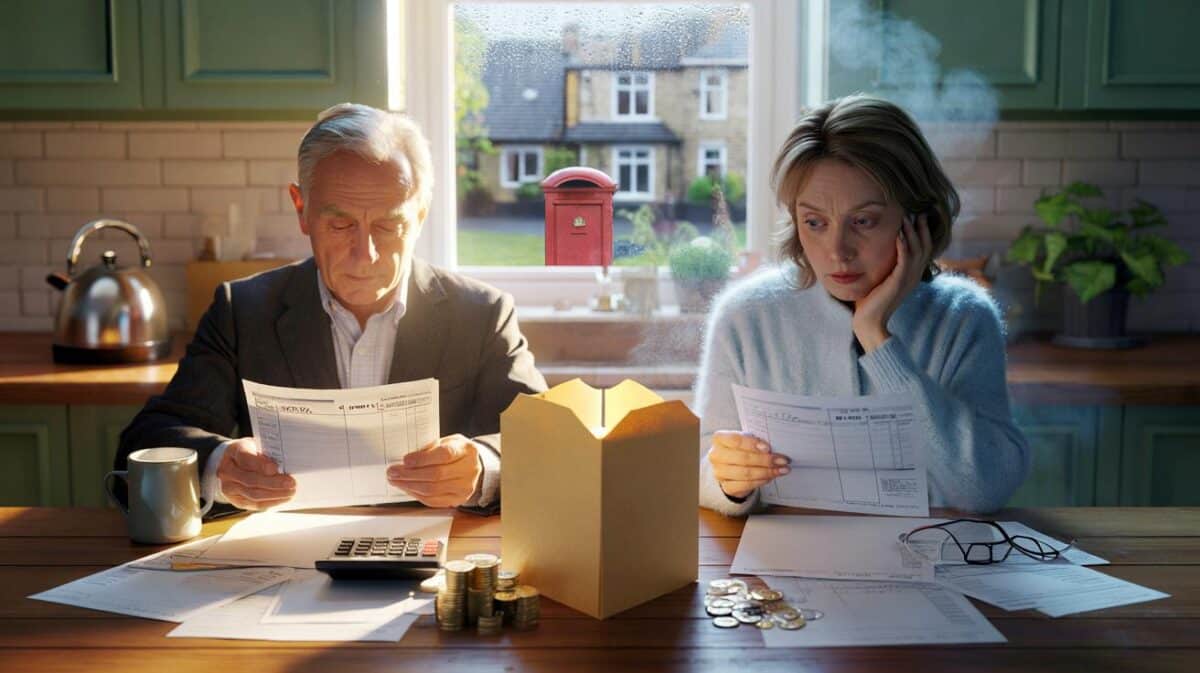

You can feel it if you pay attention: a light sting in the nose when the pan smokes, a heaviness in the room after mopping, the way a scented candle seems cosy and also… thick. Scientists are now connecting those sensations to long-term harm. In multiple countries, teams tracking households have seen the same pattern. Where indoor air is dirtier — especially from solid fuels, gas cooking, or heavy use of sprays — rates of heart disease and lung cancer rise.

It’s not a niche problem. WHO estimates millions of deaths each year tied to household air pollution, with heart disease and lung cancer among the biggest drivers. That’s the global picture; the home version can feel local and intimate. One pan fried too hot, one gas hob flaring blue, one winter of closed windows and long evenings by the wood burner. Tiny particles, gases like nitrogen dioxide, and sticky chemicals form a cloud you don’t notice until someone opens a door and you feel the fresh air slide in. **The risk doesn’t live only in big cities; it lives in the habits we repeat indoors.**

There’s a simple, slightly brutal detail: particles fine enough to float in your kitchen can also slip into your blood. Once there, they spur inflammation, disrupt blood vessel linings, and encourage the plaques that harden arteries. That’s the heart disease link. In lungs, researchers describe a different trigger. Airborne particles don’t just irritate; they can inflame and “prime” cells that already carry quiet mutations from age or past exposures. Over time, that priming can coax the wrong cells to grow. It’s not just smokers, not just heavy woodsmoke users. It’s the rest of us, too, slowly marinating in indoor haze. The house becomes a small ecosystem — and your body is part of it.

Small fixes with big health payoffs

Start at the stove. When you heat oil, use a lid for the first minute to catch the initial plume. Cook on the back burner and put the extractor fan on high before the pan gets hot. Open a window on the opposite side of the room to create a short cross-breeze. If you can, use induction or an electric hob for most tasks and keep gas for quick jobs. A portable HEPA purifier near the kitchen helps during frying or roasting. These are tiny moves. They shave off peaks that matter.

Cleaning next. Trigger sprays atomise chemicals you then wear on your lungs. Switch to wipes or diluted solutions you pour rather than spray. Go fragrance-free if you can stand it. Ventilate for ten minutes after mopping. Rethink candles and incense as weekend treats, not nightly rituals. We’ve all had that moment when the room smells too lived-in and we reach for something perfumed. Let the air in first. Let’s be honest: nobody really does that every day. Try for most days, most weeks. The wins add up.

Here’s what a respiratory consultant told me after we watched a kitchen spike during a simple stir-fry:

“You don’t need a perfect home. You need a slightly better one, most of the time. That’s enough to move the needle on risk.”

- Vent early: fan on high before heat, window cracked for cross-flow.

- Lower the smoke: lids, moderate heat, oils with higher smoke points.

- Filter the peaks: HEPA purifier in the cooking zone during hot jobs.

- Choose quieter air: induction where possible, fewer sprays, fewer flames.

- Keep it clean: wash filters, vacuum with a HEPA and change bags on schedule.

The home as a health system

Think of your space less as a container and more as a living device that breathes with you. Change the inputs, and the outputs change. When researchers study thousands of homes, they see the same story: indoor air is often dirtier than outdoor air, especially in winter, and the sources are surprisingly ordinary. Cooking. Heating. Cleaning. We’re not going to stop doing any of it. Yet a handful of practical tweaks lower exposures that push the body toward disease over years, not days. That’s the hidden gift of the new evidence — it hands us levers we can actually pull. **Prevention looks boring because it’s a string of small choices.** The irony is those choices are what reshapes risk. Not a gadget. Not a miracle filter. Just better air, more often. The kind that lets your heart and lungs work on what matters: living.

| Key Point | Detail | Interest for the reader |

|---|---|---|

| Everyday indoor air links to heart and lung risk | Studies connect home particles and gases to higher rates of heart disease and lung cancer | Turns routine habits into manageable health levers |

| Peaks drive harm | Cooking, cleaning and flames cause short, high spikes that stress the body | Target the peaks to cut risk without changing your whole life |

| Small changes work | Vent early, reduce sprays, use lids, consider induction, add HEPA near the hob | Simple, affordable steps with immediate payoffs |

FAQ :

- Is my gas hob really a problem?Gas cooking produces nitrogen dioxide and ultrafine particles that can irritate airways and add to long-term risk. Venting well and using lower heat helps, and switching to induction cuts the source entirely.

- Do air purifiers actually help?HEPA purifiers capture fine particles during cooking or dusty chores. Place one near the source and run it on high during peaks, then lower. They don’t remove gases, so ventilation still matters.

- Are candles and incense unsafe?Used occasionally, they’re a minor slice of exposure. Burn less often, choose unscented or cleaner-burning options, and ventilate. The daily habit is where risk creeps up.

- What’s the single best change I can make?Use your extractor fan on high before the pan heats and crack a window opposite. That one-two move cuts the biggest spikes fast.

- How do I know if my home air is bad?Low-cost PM2.5 sensors can reveal spikes during cooking or cleaning. You don’t need perfect accuracy — you need a feedback loop that nudges better habits. **Data that changes behaviour is the best kind.**

How strong is the evidence vs confounders like smoking, outdoor pollution, and socioeconomic status? Correlation ≠ causation. Do the cited studies control for these, and do they show a dose–response with PM2.5 peaks?

So my cozy candle-lit pasta nights are secretly a cardio hazard? Guess I’ll be romancing the extractor fan instead. Any tips for renters with loud-as-a-bus hoods and drafty winodws?